A family visit to Falun in Sweden. Today the skies are clear, but three centuries ago the air here was so thick with smoke and fumes that the heavens were rarely seen.

When Carl Linnaeus travelled through Dalarna in the summer of 1734, he wrote of Falun’s air as foul and suffocating. It was then one of Sweden’s most important towns, its wealth pulled from the ground. Silver, gold, iron, lead, sulphur and zinc all lay in the ore, but copper was king. Everyone wanted it, for coins, roofs, bells, weapons, pots, and wires. At its height the Falun Mine produced two-thirds of the copper used in the western world.

To reach pure copper, the ore had to be roasted and smelted over and over. The sulphur drifted upwards as choking smoke, the iron became waste slag, and the rest was sold. In time six million tons of sulphur dioxide were released into the air. The pollution was so extreme that it cut down bacteria and disease, and the townsfolk lived longer than elsewhere, though in poisoned air.

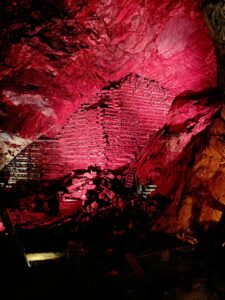

Archaeology shows that ore was being dug here at least by the late eighth century. Early mining was mostly done in open pits, where the work was brutal but less deadly. By the seventeenth century the shafts ran deep, and accidents multiplied. Records tell of miners killed by falling ore, by collapsing shafts, and by slips in the dark. The most famous disaster came in 1687, when the ground gave way and the vast crater known as the Great Pit was formed.

In the weeks before Midsummer that year, miners heard the earth groan and creak, but the work went on. Then on Midsummer Day the walls between the chambers gave way with a roar, swallowing the mine. By sheer fortune it was a holiday and no one was inside at the time.

The ore began to run out in the eighteenth century and the mine was abandoned for decades, only to reopen in the nineteenth. Today it is no longer a place of smoke and danger but a UNESCO World Heritage site, and one of Sweden’s most striking monuments to its industrial past.

Leave a Reply