An image drifted across my feed this morning: a mugshot of a certain former prince. Briefly amusing, obviously fake, the work of some obliging AI dressed up as reality. Elsewhere, a Facebook post from the Moorland Association offered something far less harmless1‘Moorland Association’. 2026. Facebook.com <https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0oQ7Ur4TJdcsaKfig7WPvURyzmFUw1UbaoQSnF5paCaVrJvtgHNPkdk4QtQWj2nYGl&id=100057094584813&_rdr> [accessed 21 February 2026]2Beeson, Rob. 2026. ‘How “Burn-To-Rewet” Cuts Methane Emissions by 95%’, Moorland Association <https://www.moorlandassociation.org/post/how-burn-to-rewet-cuts-methane-emissions-by-95> [accessed 21 February 2026]. A polished infographic declared, with confident certainty, that ‘The “Burn-to-Rewet” Method Cuts Methane by 95%.’ Slick design, bold colours, scientific language. Authority by appearance alone. Also AI generated.

The claim rests on a 2025 study by Cui et al., cited just prominently enough to sound definitive3Cui, Shihao, Haonan Guo, Lorenzo Pugliese, Claudia Kalla Nielsen, and Shubiao Wu. 2025. ‘Controlled Burning of Peat before Rewetting Modifies Soil Chemistry and Microbial Dynamics to Reduce Short-Term Methane Emissions’, Communications Earth & Environment, 6.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02336-8>. What the infographic neglects to mention is more important than what it includes. The research was a 90-day laboratory experiment conducted on small peat samples sealed in jars. Not landscapes. Not weather systems. Not living ecosystems. The authors themselves describe the work as conceptual and explicitly call for long-term field trials before any practical application. They even caution against using controlled burning for habitat restoration until risks such as pollution runoff are understood. None of this survives the journey into the infographic.

The MA further argues that restored bogs may be “worse for the climate” than drained peatlands for more than a decade because of methane emissions. The wider scientific picture is less dramatic and far more inconvenient to that argument4Zhang, Xiao, Minna Ots, Eleanor Johnston, Kathryn Brown, Nigel Doar, and others. 2025. ‘Peatland Restoration Is Anticipated to Provide Climate Change Mitigation over All Time-Scales: A UK Case-Study’, Environmental Research Communications, 7.11 (IOP Publishing): 115011 <https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ae14bb>. Restoration modelling consistently shows substantial overall emission reductions. Methane may rise temporarily, but the sharp fall in carbon dioxide loss and particulate carbon export means rewetted peat almost always produces a lower net warming effect than degraded land. The headline isolates one gas and ignores the balance sheet.

Mechanical cutting is presented as a lurking danger, leaving behind “brash” that supposedly fuels methane release and catastrophic fires. Research does confirm that cutting redistributes fine fuels into the litter layer however large-scale studies in Scotland suggests that the link between “stopping burns” and “catastrophic mega-fires” is not as direct as the MA suggests5Fielding, Debbie, Robin J. Pakeman, Scott Newey, and Stuart W. Smith. 2025. ‘The Impact of Moorland Cutting and Prescribed Burning on Early Changes in Above‐Ground Carbon Stocks, Plant Litter Decomposition and Soil Properties’, Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 6.3 (Wiley) <https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.70112>.

Burning itself is framed as climate safe management. Scientific literature paints a harsher picture. Fire on dry peat can trigger phosphorus release and mobilise toxic metals such as cadmium and arsenic once rewetting begins6Cui, Shihao, Haonan Guo, Lorenzo Pugliese, Claudia Kalla Nielsen, and Shubiao Wu. 2025. ‘Controlled Burning of Peat before Rewetting Modifies Soil Chemistry and Microbial Dynamics to Reduce Short-Term Methane Emissions’, Communications Earth & Environment, 6.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02336-8>. Smouldering peat fires may persist for weeks, quietly consuming the carbon stores restoration is meant to protect. The risks are neither theoretical nor trivial.

The laboratory finding of reduced methane is genuinely interesting. It may even prove important one day. Using it to justify widespread field burning now is, at best, premature and, at worst, opportunistic.

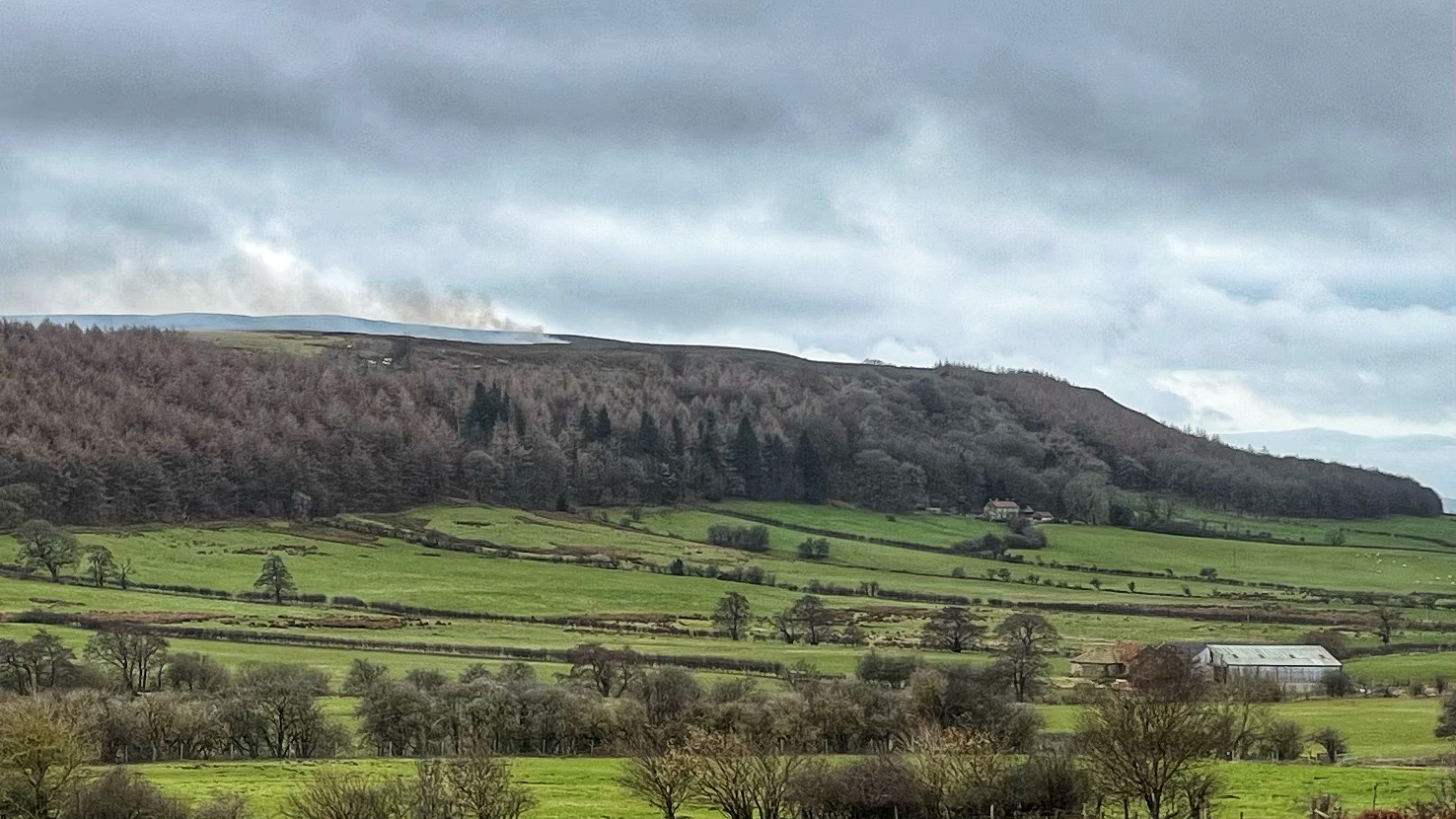

Meanwhile, smoke rises again from Warren Moor. Controlled heather burning proceeds with familiar efficiency, stripping the land back to uniformity. It is often described as tradition, a pastoral ritual tied to curlews and conservation. In truth it resembles something more industrial. Old heather is burned to force young growth, creating ideal feeding conditions for grouse ahead of the shooting season. The uplands become a carefully tuned production system for a single species, while biodiversity and peat health pay the quiet cost.

The view can be striking. The reasoning behind it is colder. This is not nature shaping the landscape, but management shaped by sport, dressed in the language of science and carried aloft on a plume of smoke.

7Kalhori, Aram, Christian Wille, Pia Gottschalk, Zhan Li, Josh Hashemi, and others. 2024. ‘Temporally Dynamic Carbon Dioxide and Methane Emission Factors for Rewetted Peatlands’, Communications Earth & Environment, 5.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01226-9>

- 1‘Moorland Association’. 2026. Facebook.com <https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0oQ7Ur4TJdcsaKfig7WPvURyzmFUw1UbaoQSnF5paCaVrJvtgHNPkdk4QtQWj2nYGl&id=100057094584813&_rdr> [accessed 21 February 2026]

- 2Beeson, Rob. 2026. ‘How “Burn-To-Rewet” Cuts Methane Emissions by 95%’, Moorland Association <https://www.moorlandassociation.org/post/how-burn-to-rewet-cuts-methane-emissions-by-95> [accessed 21 February 2026]

- 3Cui, Shihao, Haonan Guo, Lorenzo Pugliese, Claudia Kalla Nielsen, and Shubiao Wu. 2025. ‘Controlled Burning of Peat before Rewetting Modifies Soil Chemistry and Microbial Dynamics to Reduce Short-Term Methane Emissions’, Communications Earth & Environment, 6.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02336-8>

- 4Zhang, Xiao, Minna Ots, Eleanor Johnston, Kathryn Brown, Nigel Doar, and others. 2025. ‘Peatland Restoration Is Anticipated to Provide Climate Change Mitigation over All Time-Scales: A UK Case-Study’, Environmental Research Communications, 7.11 (IOP Publishing): 115011 <https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ae14bb>

- 5Fielding, Debbie, Robin J. Pakeman, Scott Newey, and Stuart W. Smith. 2025. ‘The Impact of Moorland Cutting and Prescribed Burning on Early Changes in Above‐Ground Carbon Stocks, Plant Litter Decomposition and Soil Properties’, Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 6.3 (Wiley) <https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.70112>

- 6Cui, Shihao, Haonan Guo, Lorenzo Pugliese, Claudia Kalla Nielsen, and Shubiao Wu. 2025. ‘Controlled Burning of Peat before Rewetting Modifies Soil Chemistry and Microbial Dynamics to Reduce Short-Term Methane Emissions’, Communications Earth & Environment, 6.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02336-8>

- 7Kalhori, Aram, Christian Wille, Pia Gottschalk, Zhan Li, Josh Hashemi, and others. 2024. ‘Temporally Dynamic Carbon Dioxide and Methane Emission Factors for Rewetted Peatlands’, Communications Earth & Environment, 5.1 (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01226-9>

Leave a Reply