It seems fitting to be posting this at the end of January 2026, a month that quietly marked a profound centenary. One hundred years ago, Section 193 of the Law of Property Act 1925 gave the public a legal right to access around a third of the common land in England and Wales. For the first time, the law recognised a simple but radical idea: that large parts of the countryside were for everyone1Bedendo, Federica. “‘We shouldn’t take outdoor access for granted’.” BBC News, 24 Jan. 2026. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cnvggr3jy2qo > [accessed 25 January 2026].

Today, that promise feels ordinary. A walk through woodland or across open fell seems timeless, almost natural. But this freedom was not inherited from the distant past. It was fought for, secured inch by inch, and it remains far more fragile than we like to think.

Before campaigners forced change, most rural land was entered only by permission. Access depended on the goodwill of landowners, not on public right. The paths we enjoy today did not appear by chance. They exist because people argued that nature should not be reserved for a few.

The Open Spaces Society was central to that fight, helping deliver the 1925 Act and laying the groundwork for later gains such as the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. Together, these laws shifted the balance away from purely permissive access and towards something firmer: a right to be there.

That distinction matters. Where access is a right, it is protected. Where it is merely permitted, it is vulnerable. Many well-used routes operate under “permissive access”, meaning a landowner allows entry but can withdraw it “at any time, often without consultation or warning”. A path walked for generations can vanish overnight, a gate locked, a sign erected, a link cut.

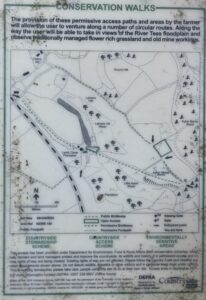

This track to the old Monument Ironstone Mine is a case in point. For a time it was a Permissive Bridleway under DEFRA conservation schemes. The gate is now padlocked, though the signage remains. Only the small print reveals that access ended in September 2011, presumably when the payments stopped.

This creates a clear imbalance. On a permissive path, as one writer puts it, “You are never truly welcome. You are tolerated.” That instability undermines our relationship with local landscapes and hits hardest those with the fewest alternatives: older people, families, and those without cars. This is about fairness as much as recreation2Ditchburn, Charlotte. “Why Permissive Access Fails: Rights, Inequality and Access to Land & Water.” PROW Explorer, 23 Jan. 2026. https://www.prowexplorer.com/blog/why-permissive-access-doesnt-really-work [accessed 25 January 2026].

Permissive access also creates an “illusion of security”. Because a path exists, it can delay the push for permanent, rights-based solutions. Voluntary agreements and paid access suffer the same flaw: they are temporary and reversible. Legal rights endure.

Even those rights face pressure. Tensions over litter and abandoned tents are real, but exclusion is not the answer. Most damage comes from ignorance, not malice. Care grows from familiarity, and familiarity requires access. Education, starting early, is key. People protect what they are allowed to love.

Our access to the countryside is a hard-won inheritance and a fragile one. The paths we walk are promises made in law and effort. They can be strengthened, or they can be lost. The next time you walk a path, it is worth remembering that it is not just a route under your feet, but a shared commitment to keep the land open for those who come after us.

- 1Bedendo, Federica. “‘We shouldn’t take outdoor access for granted’.” BBC News, 24 Jan. 2026. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cnvggr3jy2qo > [accessed 25 January 2026]

- 2Ditchburn, Charlotte. “Why Permissive Access Fails: Rights, Inequality and Access to Land & Water.” PROW Explorer, 23 Jan. 2026. https://www.prowexplorer.com/blog/why-permissive-access-doesnt-really-work [accessed 25 January 2026]

Leave a Reply